The Atomic View

Now the real fun begins

Podcast is AI generated, and will make mistakes. Interactive transcript available in the podcast post.

In case you missed it, we’re spending this year recruiting 60 schools with an ambition to transform maths outcomes for their students, and make failure obsolete.

The first dozen of these Unstoppable Schools is joining our community on Monday 23rd February, with many more gearing up to join us in March.

If you would like your school to join them:

School network leaders, use this form to learn more.

School leaders, including subject leaders, use this form to learn more.

We will build out programmes for individual teachers in the future, and if you would like to be kept informed, you can express interesting using this form.

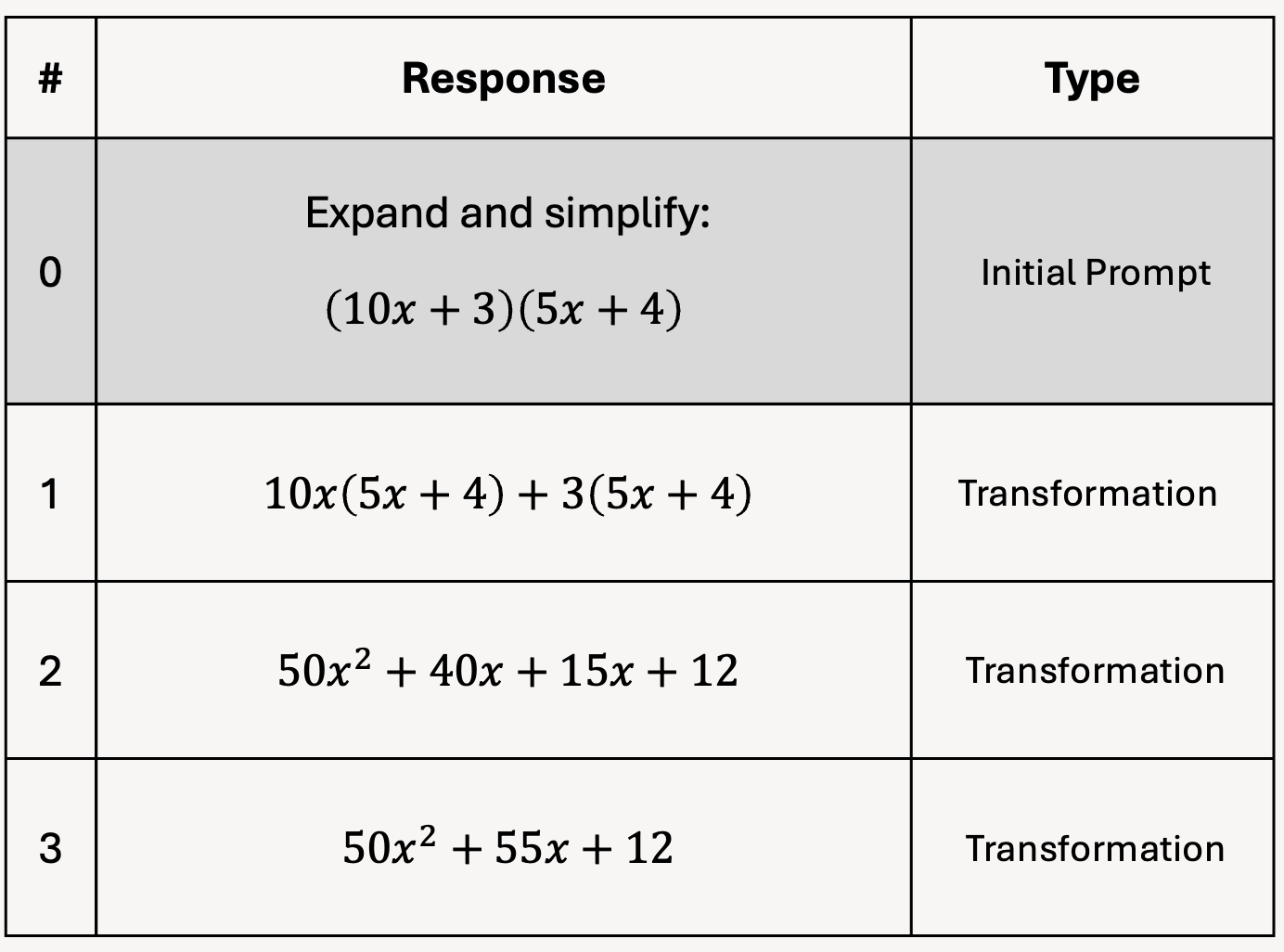

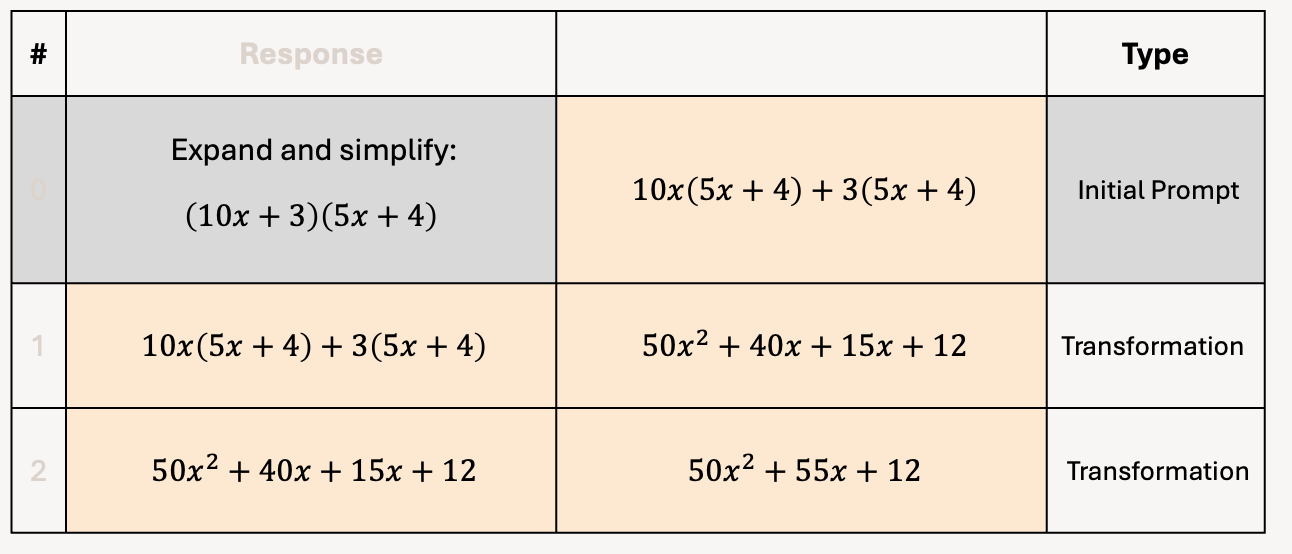

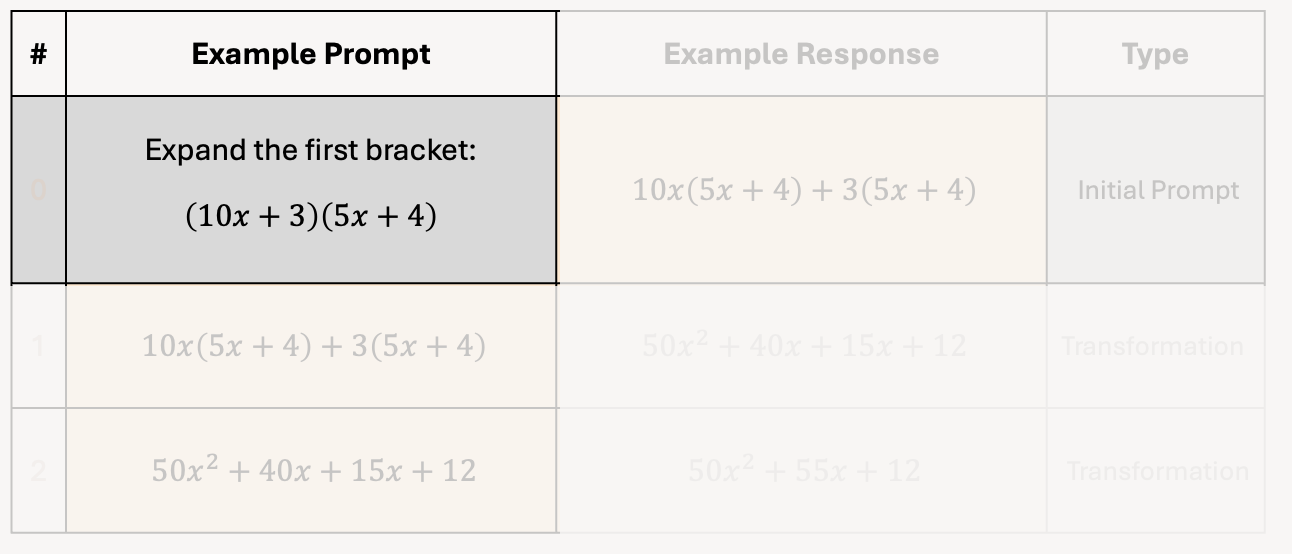

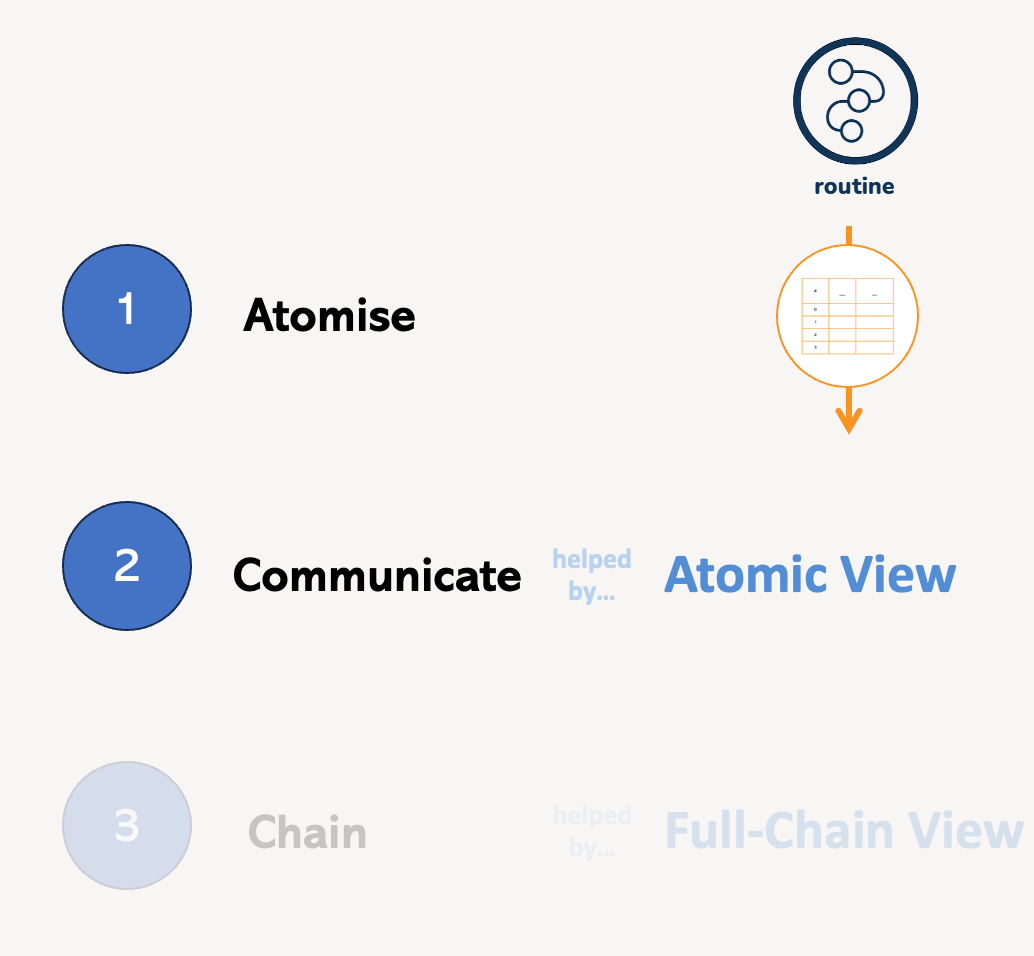

The full chain view gives us the end-to-end chain of thinking we eventually want students to be able to step through.

And it starts the process of shifting our perspective away from seeing these as just steps in a process and towards viewing them as mathematically meaningful atoms.

But with this view alone, that’s a little tricky.

For example… what exactly do we mean when we say that ‘this,’ here, is a transformation?

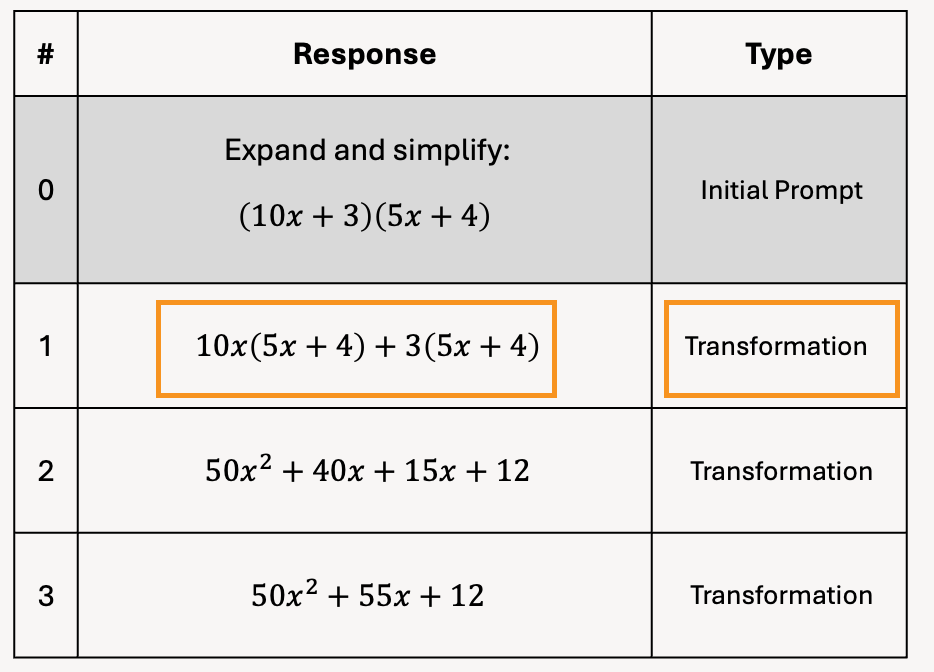

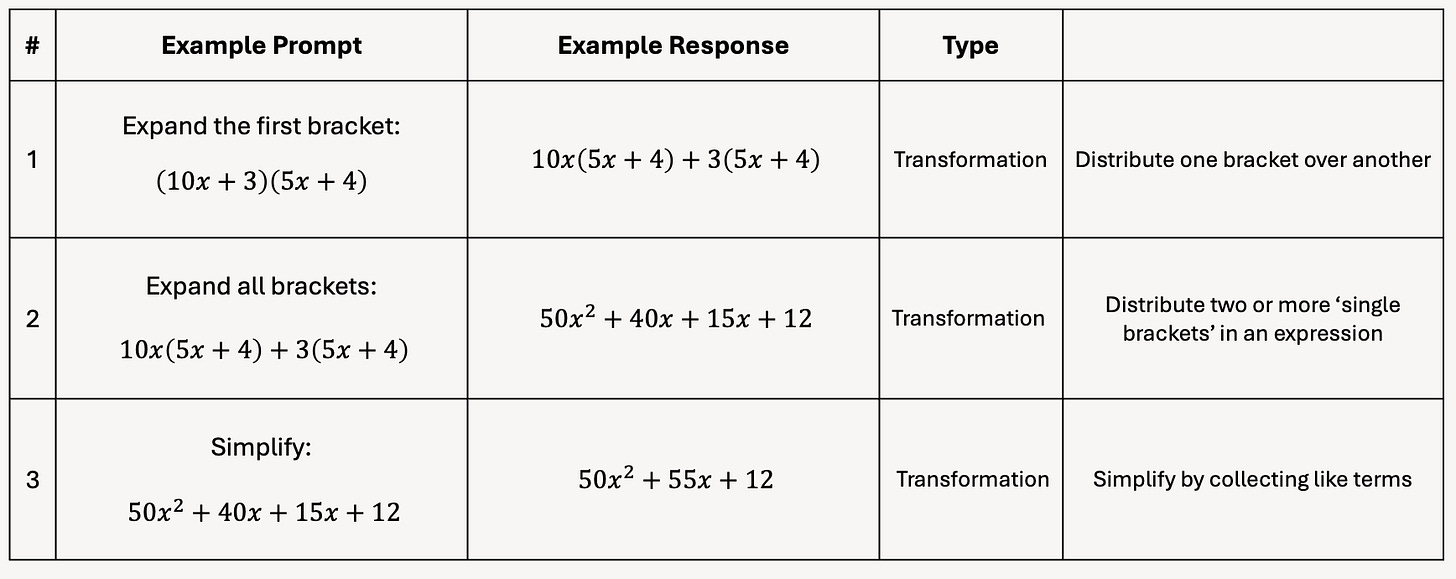

In the full-chain view it can be tricky to see exactly what the transformation concept here is. So now, the atomic view now helps us with this.

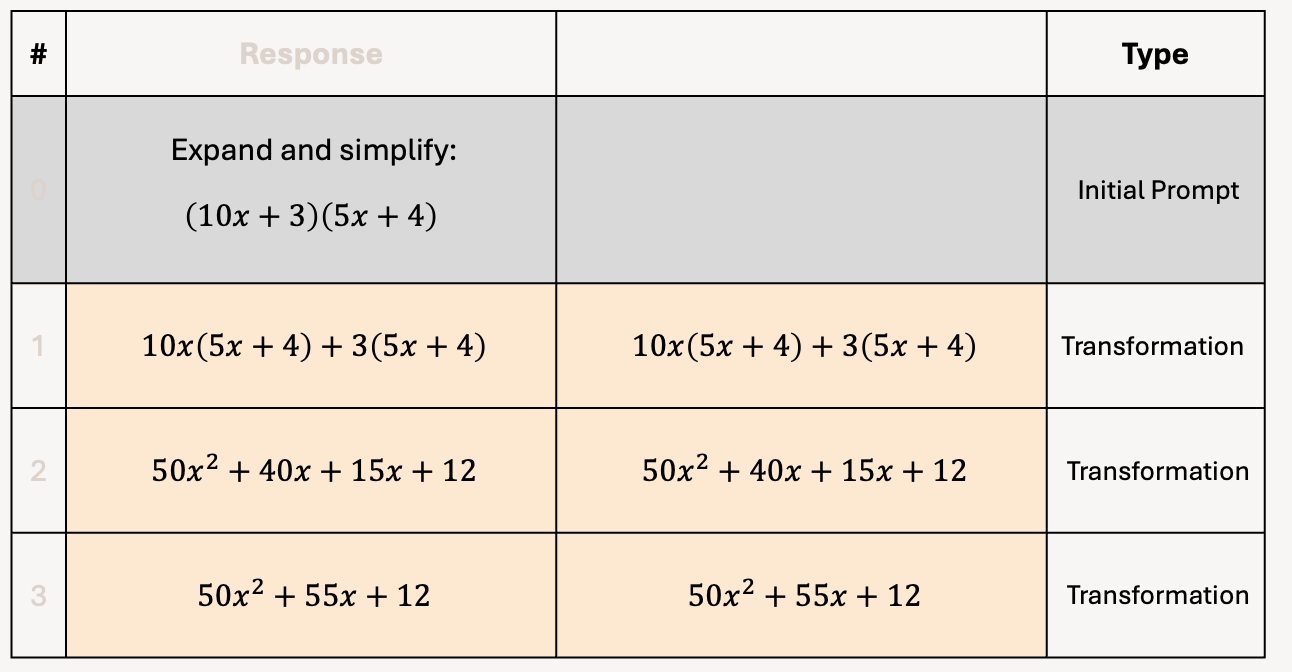

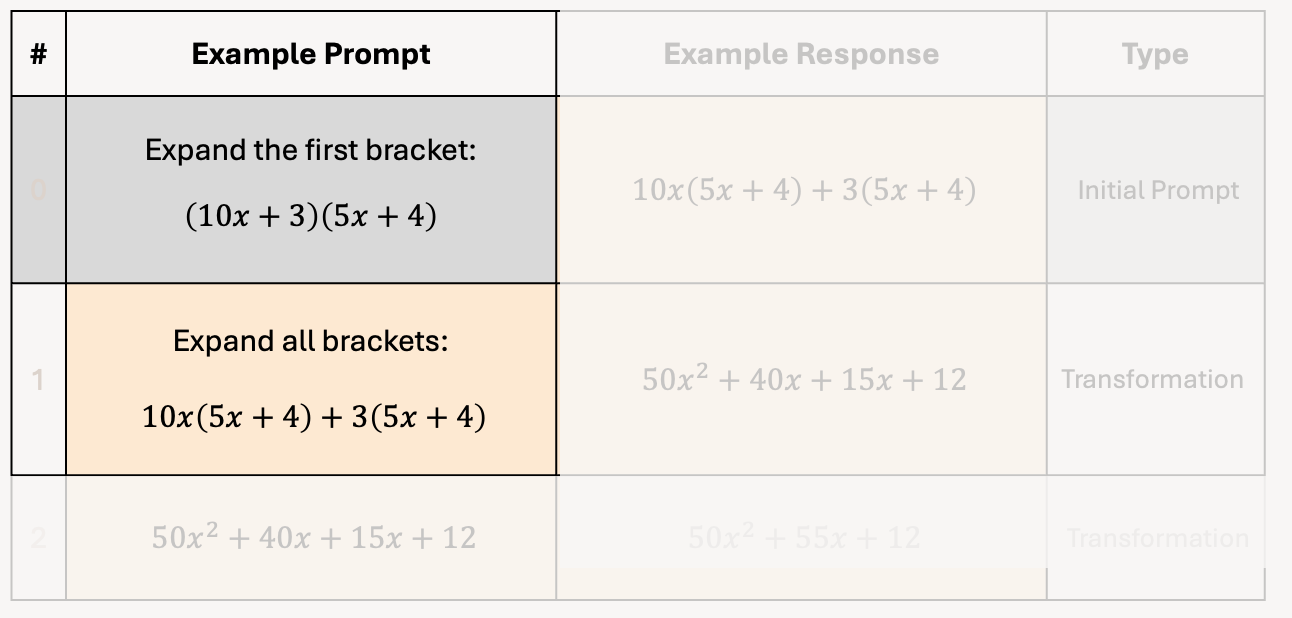

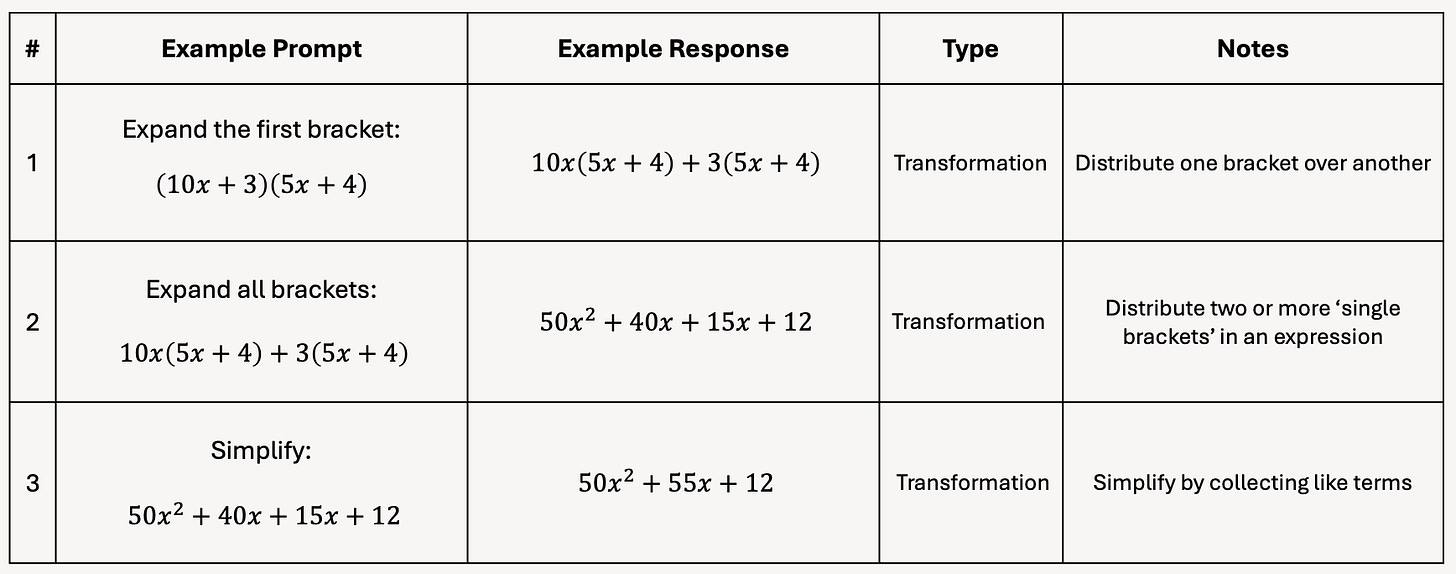

To construct the atomic view, we duplicate every atom after the initial prompt, and paste them in a new column to the right.

Then shift them up one row.

And then delete the bottom row.

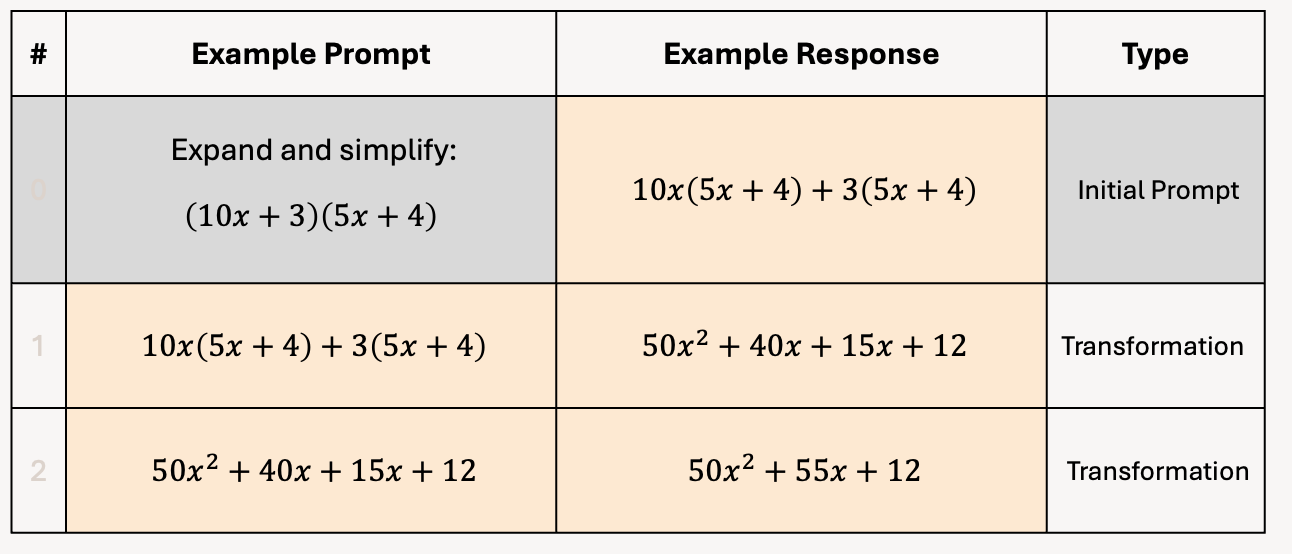

What we now have is one column for an example prompt we could give to a student, and then a second column for the response we would expect to see from them to that prompt.

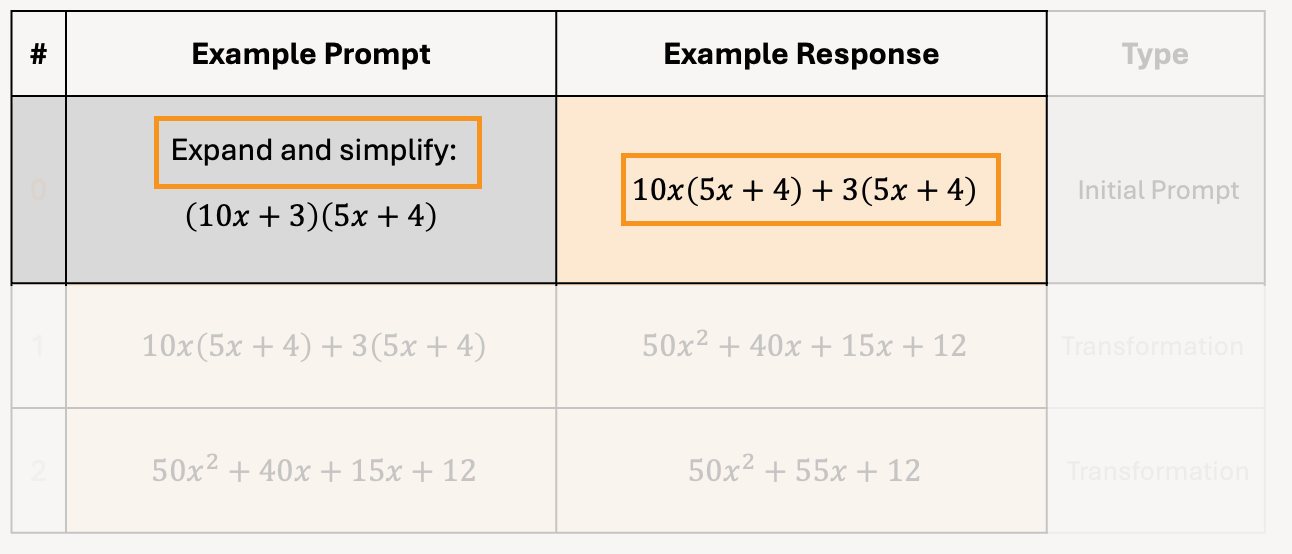

But, right now, the prompt column isn’t really showing the correct wording to produce each time the example response in the first row.

When we say ‘expand and simplify,’ this is not the response we expect.

Or, our prompt doesn’t have any wording at all.

Here, we have the artefact, but no words. It’s impossible to know how to respond to this on its own.

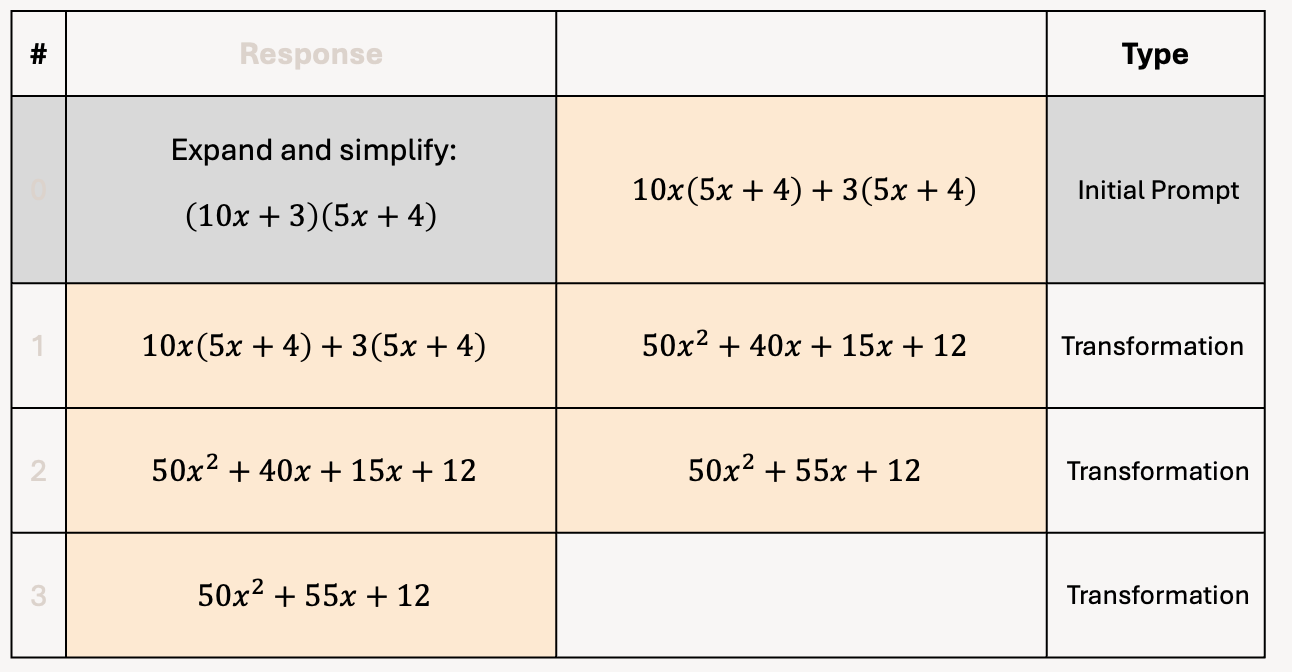

So, we need to now tweak each of the prompts so that they make sense.

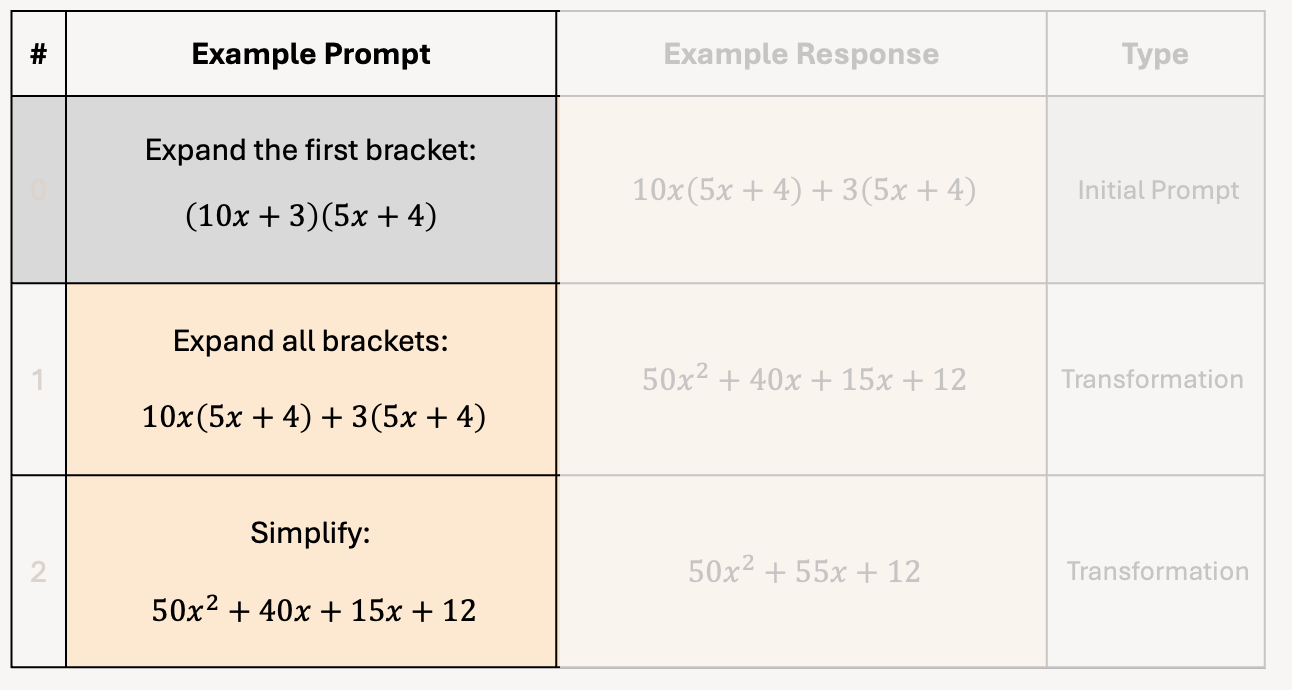

For example, the first row should now say something more like this:

And then the next row should say something more like this:

And so on.

Since the first row now shows a complete prompt and response - something that involves cognitive work - we label it with a 1 this time, not a 0 as in the full-chain view.

And for the same reason, it’s not just ‘an initial prompt’ anymore, it’s one of the four atomic elements, so we label it as such.

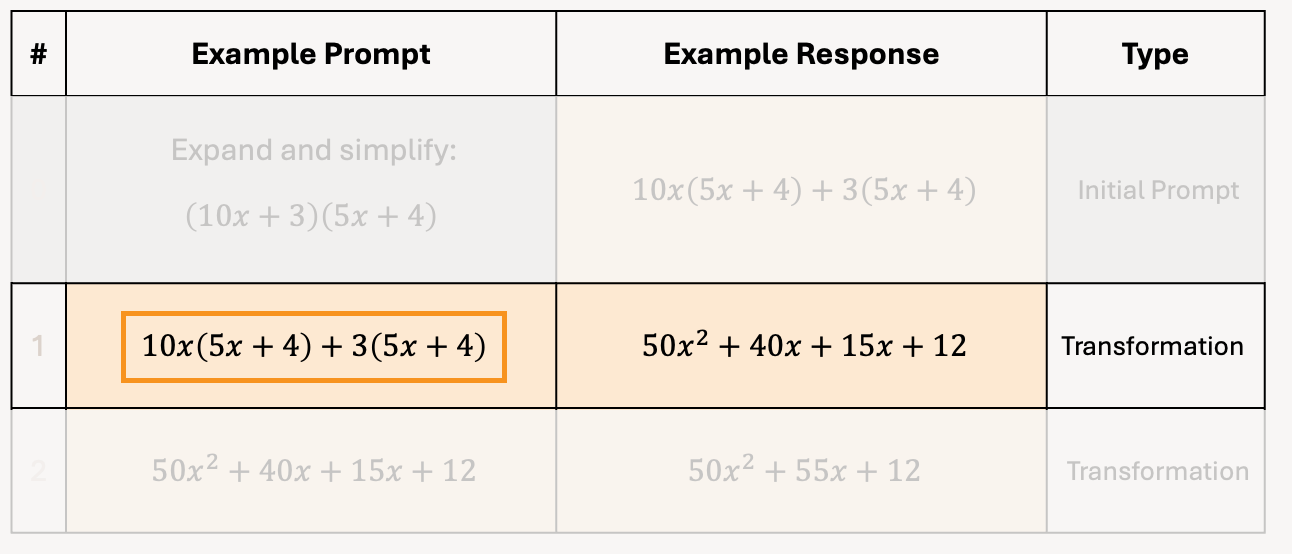

We do the same for all remaining rows:

And now each row gives us a distinct and meaningful mathematical concept; a distinct prompt we could give to students at any time, and in any order outside of the step by step, end to end process.

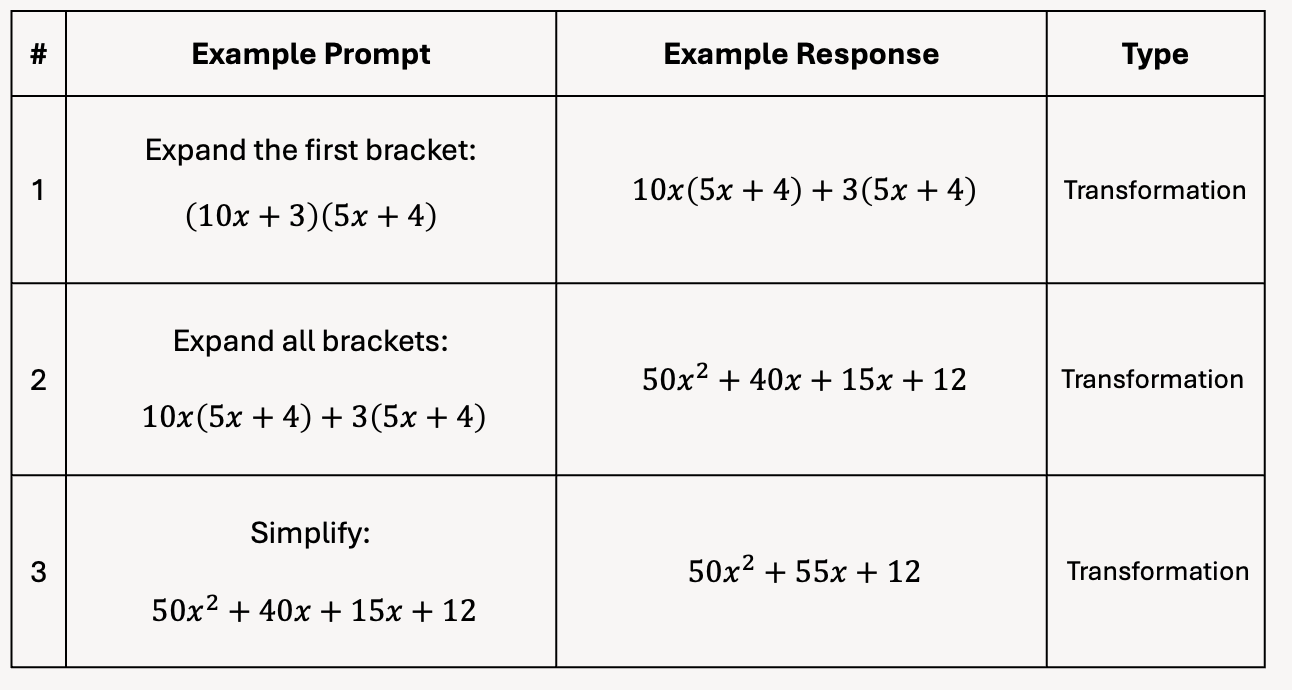

Finally, in each row what we have is just an example prompt, and associated response.

How can we describe the broader mathematical idea we’re trying to communicate?

To make that clear to us, and to our colleagues, we add a fourth column.

In this column we say in words what the general mathematical idea is that we’re trying to communicate.

We might also sometimes use this column to add any additional notes about how to communicate an atom.

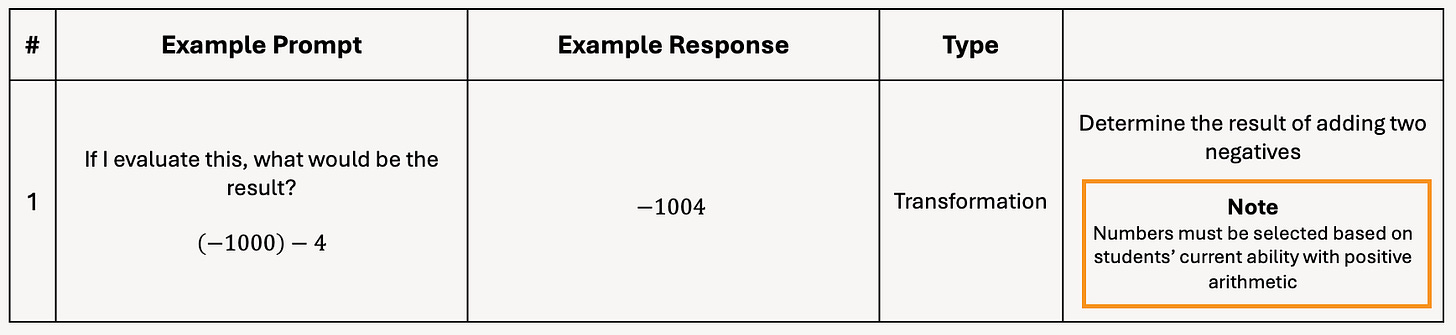

In the example below, the goal is not for students to have to work any tricky arithmetic, but to see that the sum of two negatives is always negative, so the numbers should be chosen based on students’ current ability with positive arithmetic.

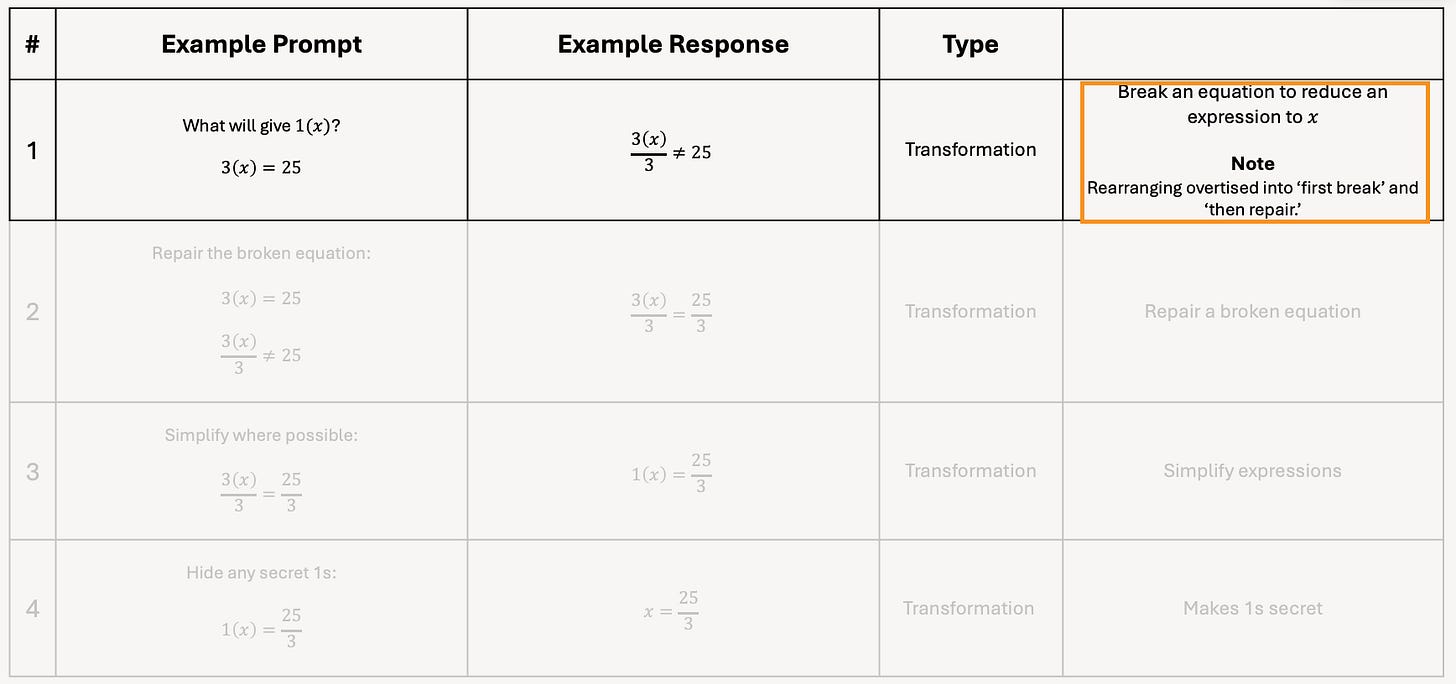

Or we sometimes add in why we chose to include an atom at all in the routine… especially if it’s uncommon.

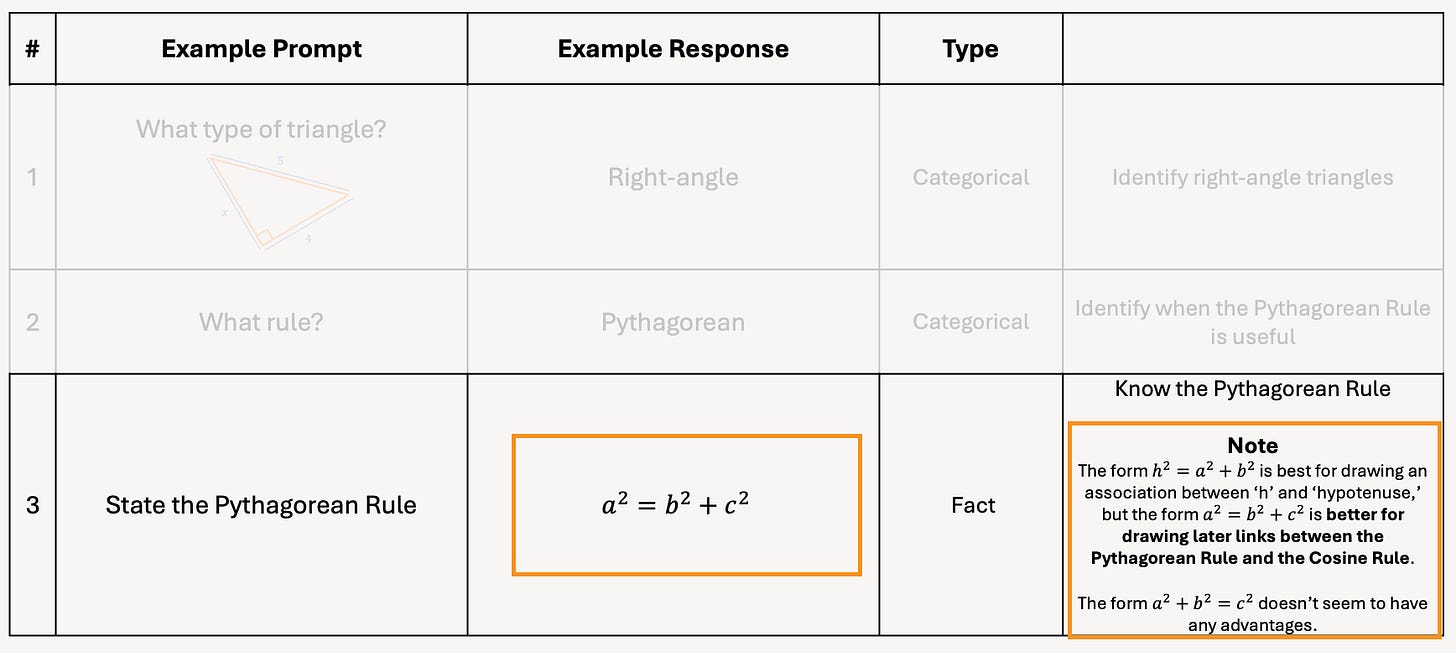

Or when choosing a particular example prompt or type of response, again we might choose to explain that choice here.

Since this column is doing a lot of work, we give it the fairly generic heading of ‘notes.’

Now, each of these atoms can be a complete learning objective, all on its own, operationalised to be an observable behaviour: prompt and response.

Instead of viewing these atoms as just steps in an end-to-end process – one that we must work through in full, start to finish, we can instead explore each of them thoroughly – and communicate them faultlessly – using the methods we have already explored.

Once we have communicated each atom, we can then finalise the cognitive routine via chaining.

Next, we’ll dive a little further into our options for atomic communication, and before moving on to look at our options when chaining.