Routine Atomisation

Step 1 to guaranteeing success, and how to do it

Podcast is AI generated, and will make mistakes. Interactive transcript available in the podcast post.

In case you missed it, we’re spending this year recruiting 60 schools with an ambition to transform maths outcomes for their students, and make failure obsolete.

School network leaders, use this form to learn more.

School leaders, including subject leaders, use this form to learn more.

We will build out programmes for individual teachers in the future, and if you would like to be kept informed, you can express interesting using this form.

Previously, we saw how to identify cognitive routines:

Some Children Will Always Fail

Podcast is AI generated, and will make mistakes. Interactive transcript available in the podcast post.

As noted, learning a multi-step process is difficult for most students, and so teaching cognitive routines is one of the most difficult things we will attempt to do, with the greatest risk of, and many opportunities for, failure.

While traditional methods can yield some benefits, are can even be highly suited to certain niche cases, in our experience, none of them is sufficient on their own to guarantee success for 100% of students, 100% of the time.

This is in part because, on their own, none of these techniques lends itself automatically to creating logically faultless communication.

So, we instead favour an alternative approach, one which begins with atomisation.

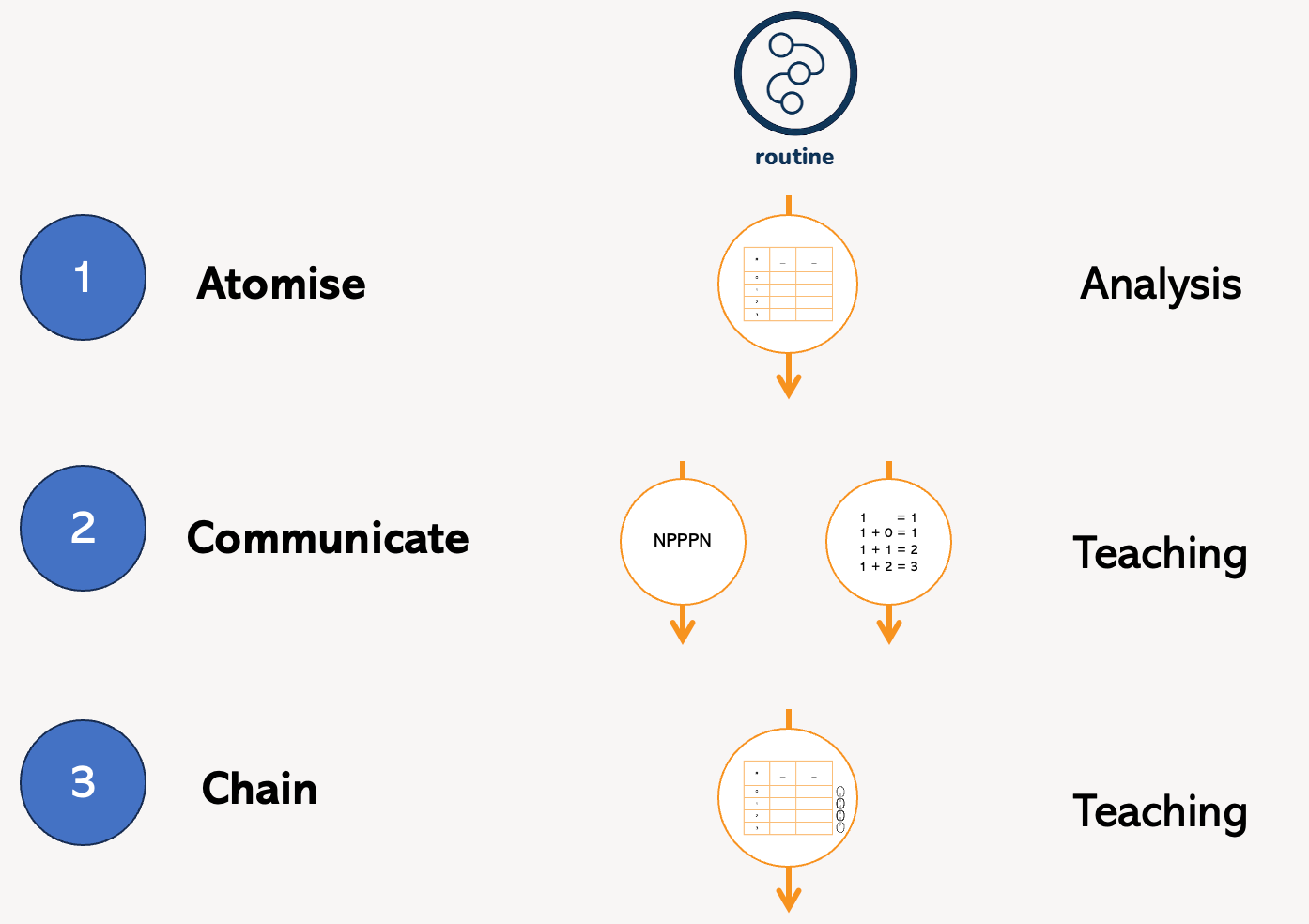

The most interesting misconception about atomisation is that it isn’t exactly a ‘teaching method;’ instead, it’s an analytical method.

This is a confusion we often see in wider education discourse. It seems that this confusion is at least partly due to slim or partial explanations of atomisation that exist elsewhere.

As an analytical method, atomisation blows wide open a whole series of options we might never otherwise realise exist, and which collectively make successful learning all but guaranteed for all students.

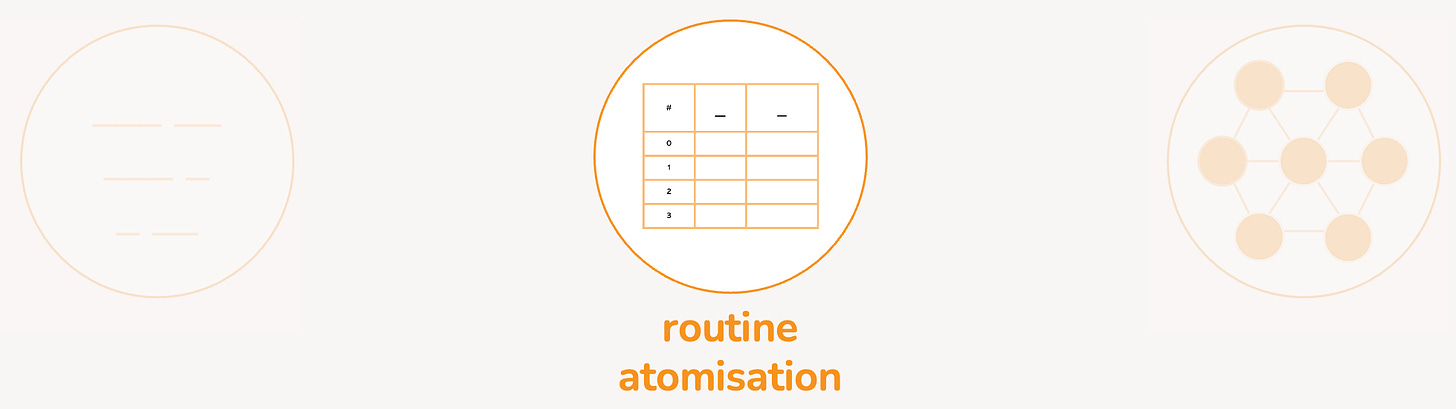

There are three different kinds of atomisation. Since here we’re focused on how to teach cognitive routines, the type of atomisation we will be looking at is called routine atomisation.

And we’ll be following a three-stage process:

First, atomise.

Then, communicate.

And then, chain.

If step 1 is the method of analysis, then it’s steps 2 and 3 that will be the methods of teaching.

Routine atomisation is fairly straightforward.

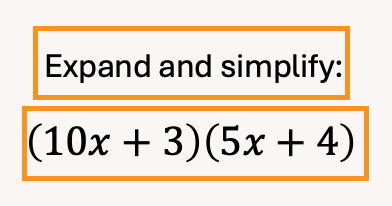

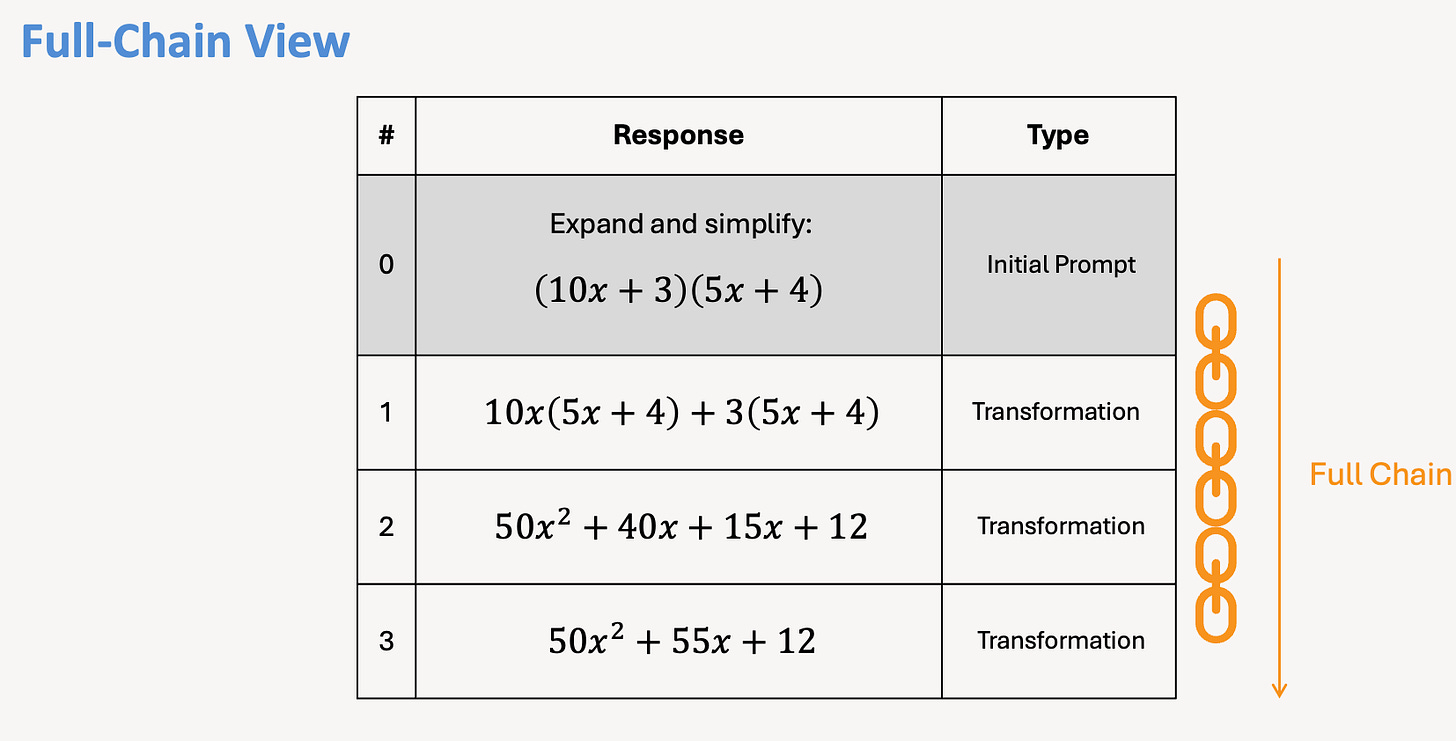

We’ll use the example of expanding a pair of brackets to begin.

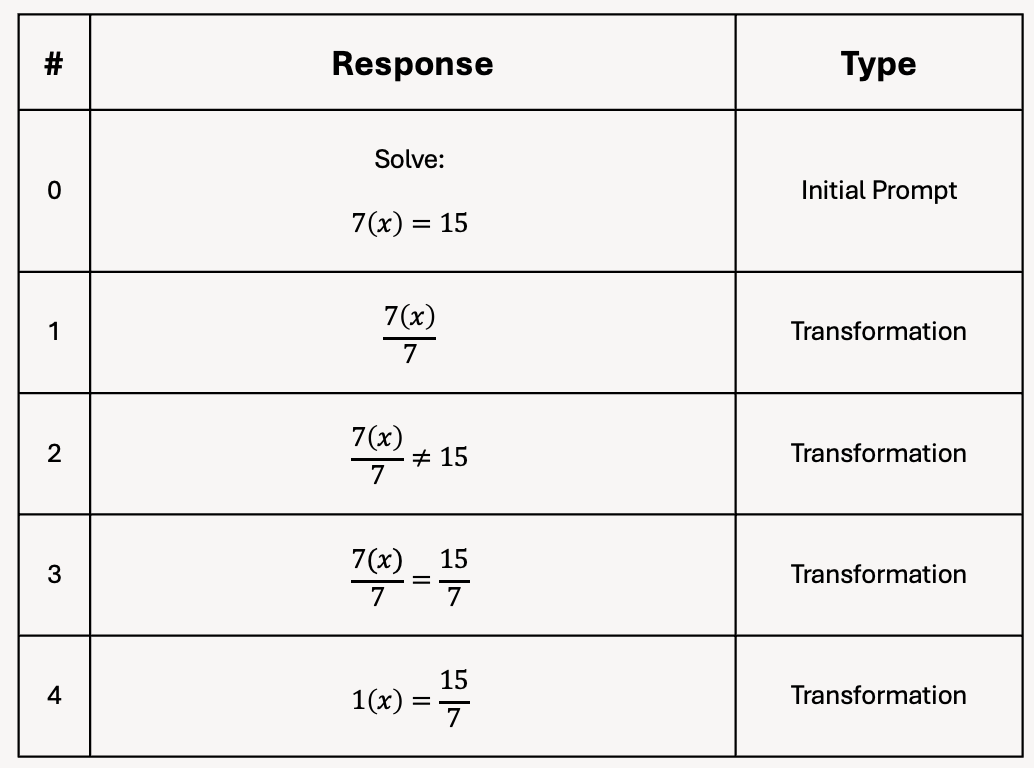

First, write out your initial prompt.

This is the task, exercise or question – the words plus artefact – that you want your students to be able respond to.

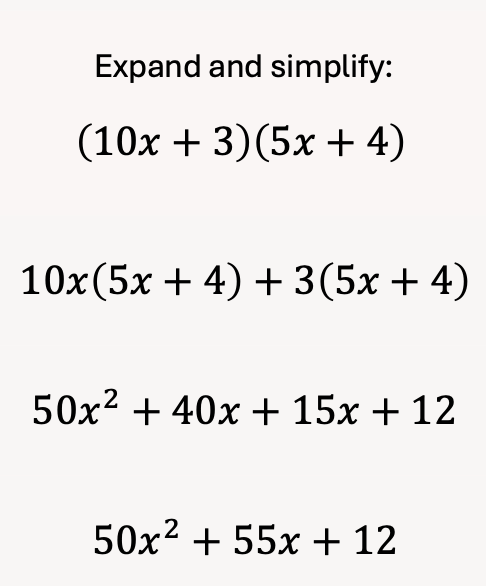

Then, just write out the step-by-step process as you would normally work through it.

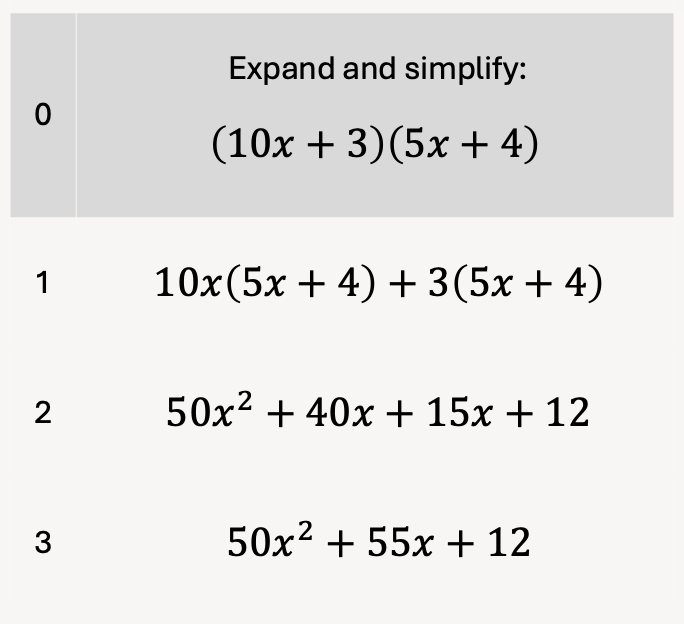

From here, label the initial prompt with a zero, then number each step.

So far, so, common.

What happens next is what’s going to differentiate this from traditional methods.

We’re going to stop talking about these as steps in a process.

Instead, we are going to start referring to them as individual atoms, and since they are atoms, each one must be one of the four elements.

So, we state which of the four elements, which type of atom, each one is.

In this case, each atom is a transformation.

Why does this tiny change in perspective create so much impact?

It creates so much impact for several reasons, and we’ll be exploring each of them over the coming weeks. Our hope is that, by the end, if a colleague tells you ‘this is nothing new,’ or ‘I already do this,’ you will have everything you need to gently probe the veracity of that claim.

We’re already in place to pick off the first two in this list.

The first reason is that what used to be just yet another ‘step in a process’ is now a mathematically meaningful idea all on its own.

A second reason is that, once we know what type of atom each idea is, then we automatically know how to design logically faultless communication for it.

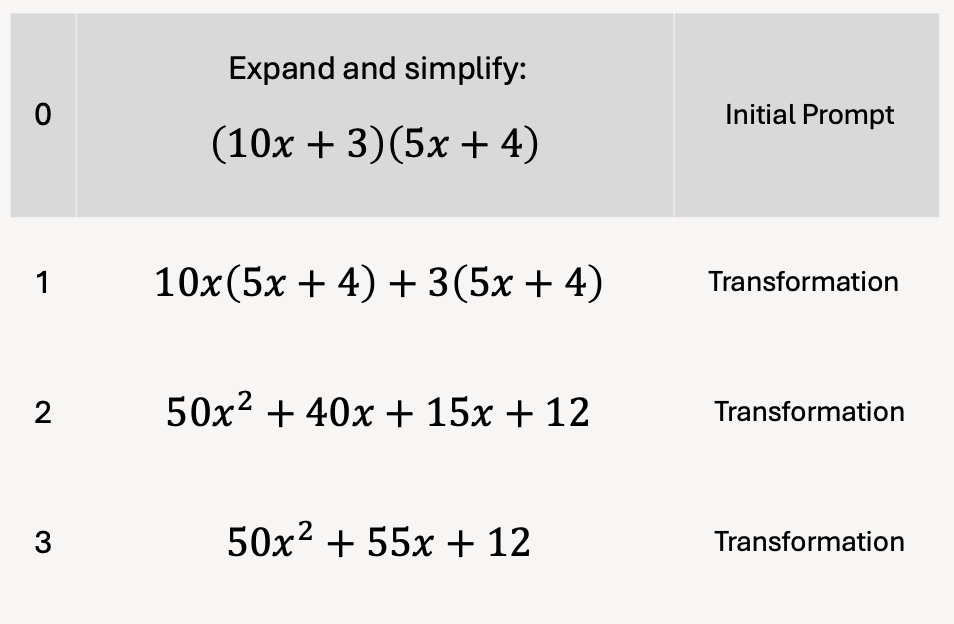

Now, the example above has been constructed using a simple template.

It’s a simple template, but whether working on computer or working by hand, we strongly encourage you to use it when atomising.

We went through many design iterations before learning that this is the best way to set out routine atomisation.

It presents what we call the full-chain view.

This is the start to finish process and working that we want students to reproduce, and this view will help us when we come to stage three, chaining.

The full-chain view will also help us to complete a second template: what we call the atomic view that will aid stage two, communication.

But it is always easiest to start by creating the full chain view and then use that to quickly construct the atomic view later.

We’ll wrap up with several more examples of cognitive routines that have been atomised using this template, including:

Solving one-step equations

Sharing in a ratio

Adding fractions

Solving an algebraic angle problem

Calculating the output of a compound function

For each, where the methods are unusual, we’ll also offer some explanation as to the method selection.

For example, how and why have we turned the supposed ‘one-step’ equations into a routine that requires four steps? And how do the ratio and fraction routines develop mathematical meaning without relying on visual models?

This will include why we have used non-conventional symbols in places, e.g. when working with functions.

Solving One-Step Equations

The key to this is to think as al-Khwarizmi once did. What we call ‘rearranging’ is not about ‘balancing’ or ‘doing to one side what you do to the other,’ it is about…