Some Children Will Always Fail

And it's their fault, not mine.

Podcast is AI generated, and will make mistakes. Interactive transcript available in the podcast post.

Learning a multi-step process is difficult for most students.

And so, teaching cognitive routines is one of the most difficult things we attempt to do, with the greatest risk of, and many opportunities for, failure.

Traditional methods try to meet this challenge using techniques like:

visual models, with a stress on conceptual understanding

scaffolds with guidance fading

‘small steps,’ or the idea of ‘breaking things down’ to teach a bit at a time

techniques like ‘name the steps’

worked example problem pairs, now enshrined in the language of I do / We do.

Each of these can yield benefits, but, in our experience, none of them is sufficient on their own to guarantee success for 100% of students, 100% of the time.

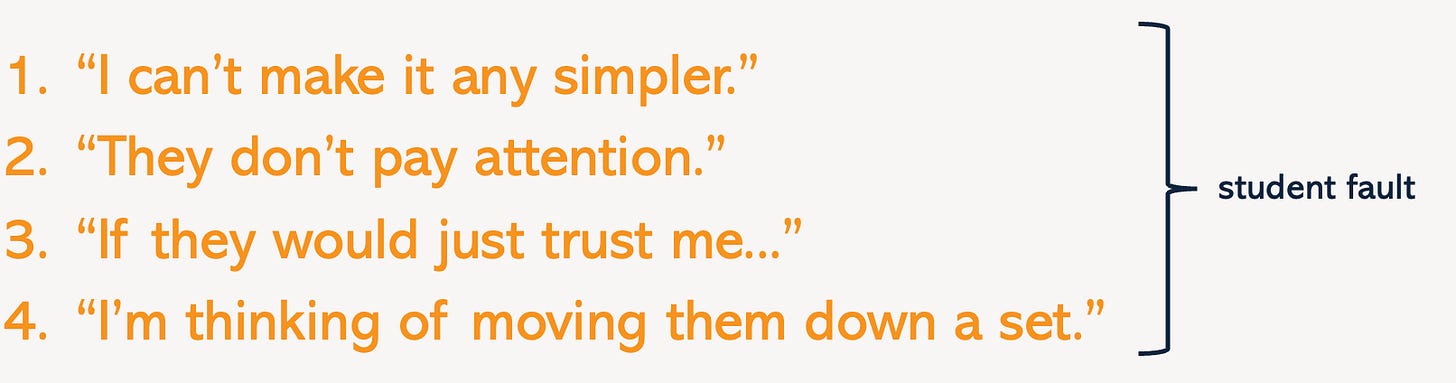

Then, when students fail, we frequently hear teachers say things to us like:

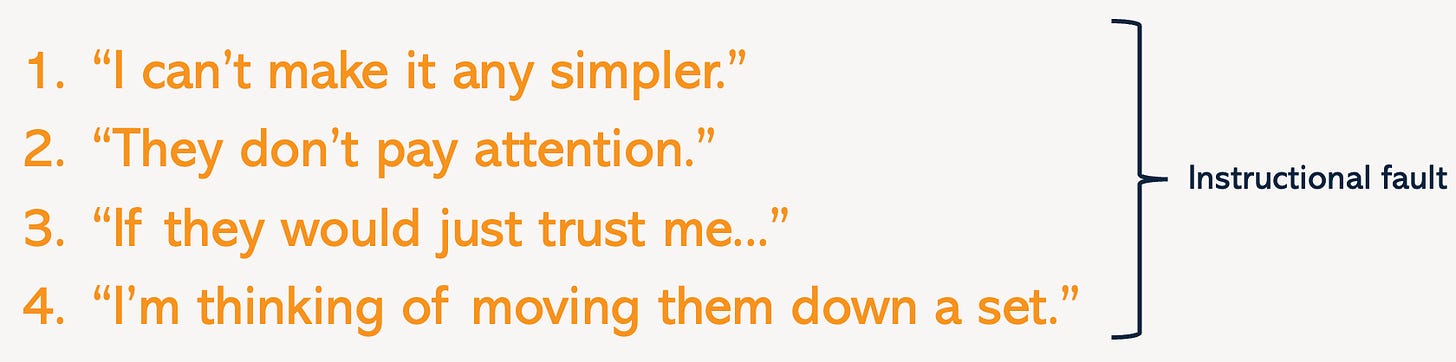

‘Look, there’s no way I could make this any simpler for them.’

‘You know what, they just don’t pay attention. When they pay attention, they do absolutely fine, but, most of the time they just don’t bother paying attention.’

‘The problem is, they just don’t trust me. If they trusted me, and just copied exactly what I did, they’d get it right, every time.’

‘I think they’re just in the wrong set. I’ve been thinking of moving them down.’

In other words, frustration and confusion around student failure leads us to only one possible conclusion: it’s their fault, not mine. I’ve done everything I possibly can, and so the fault must now lie with them.

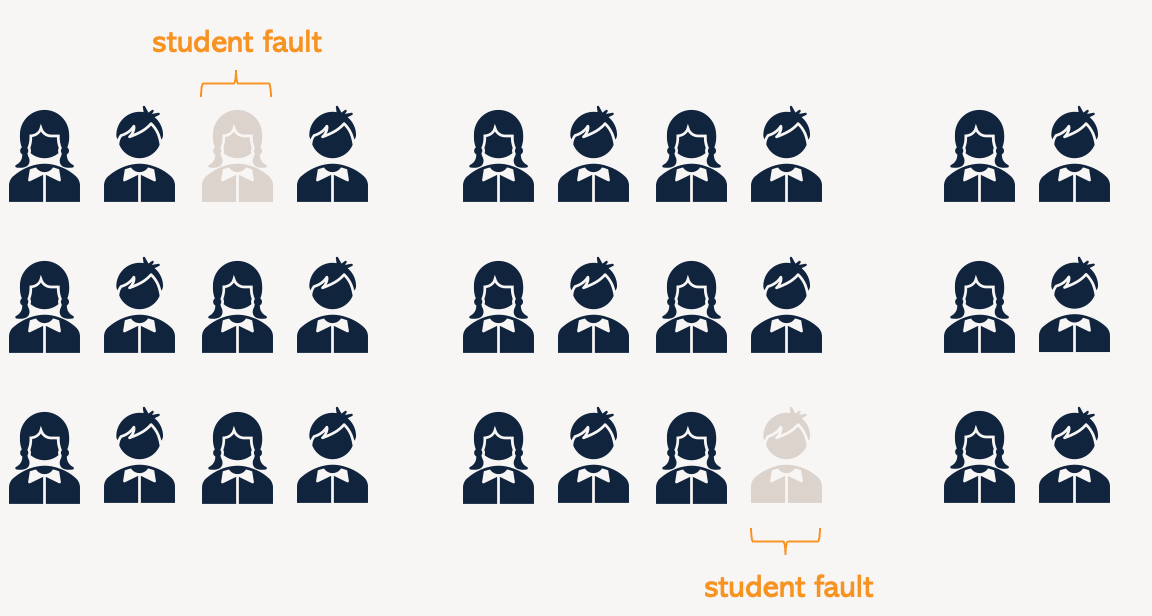

And it makes sense, because other students in the in the room are getting it, maybe even most other students. So there can’t be anything wrong with my explanation.

But when we looked at the cause of misconceptions, we already saw one way in which this logic falls down.

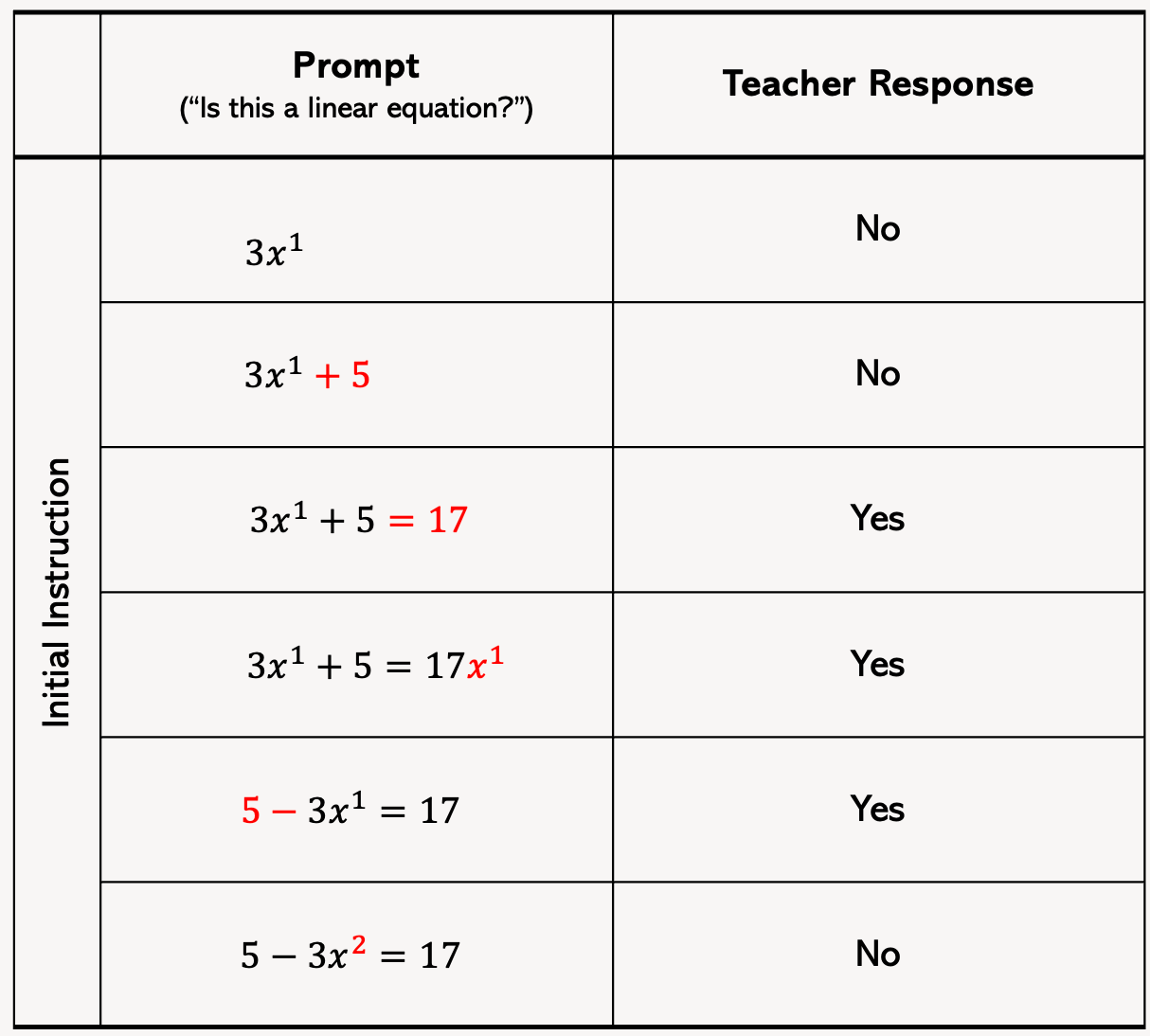

As a reminder, if I presented this sequence to communicate what we mean by ‘linear equation’

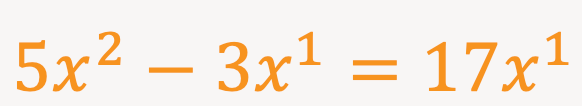

Then it’s a dice roll as to whether students in my class now say that this is linear, or not.

From my sequence, it is possible to learn the misrule that the equation is linear so long as there’s an ‘x to the power of 1’ in there.

So, some students will say that this is linear, while others will pick up on the x squared in my last negative, and they’ll say that it is not, and - this is key - both responses are logically consistent with what I presented; my fault, not theirs.

Nothing to do with intelligence, and assuming no prior knowledge, all differences in conclusion will arise purely by chance – my communication was not logically faultless, and so I laid open the chance for students to take one path or another at random.

So, the fact that most students got it and others didn’t is not evidence that my teaching was beyond reproach.

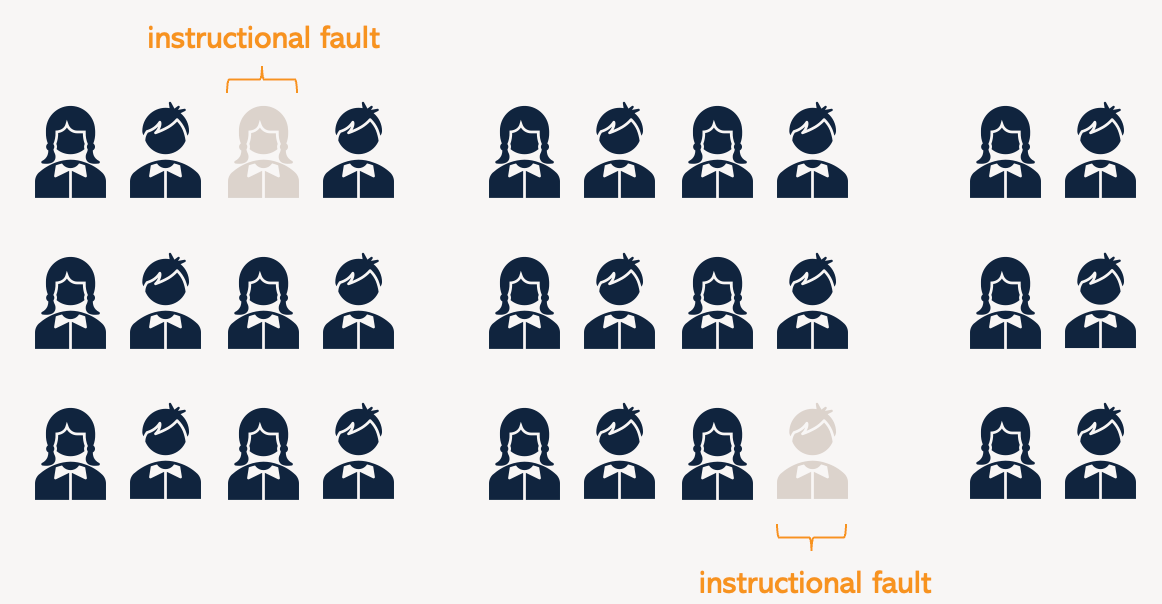

It’s still very likely that there was an instructional fault, rather than a student fault.

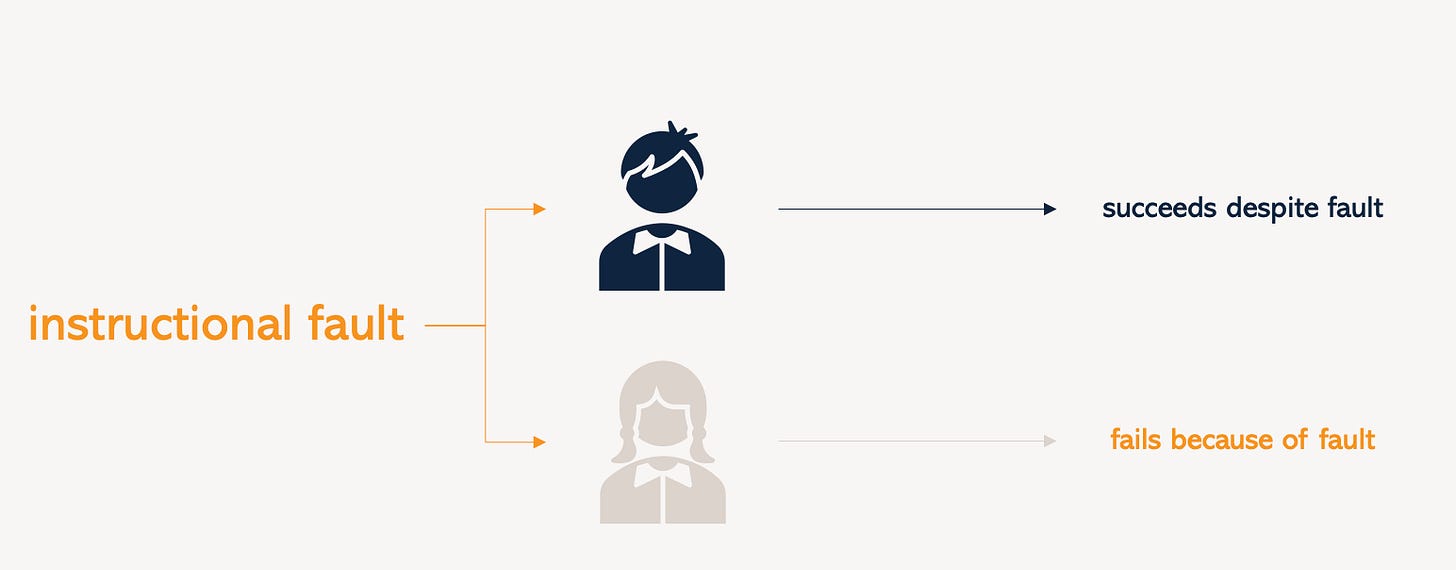

Now, as we explore cognitive routines, and routine atomisation, we’ll see new ways that some students will succeed despite imperfections in our communication, while others fail as a consequence of those imperfections.

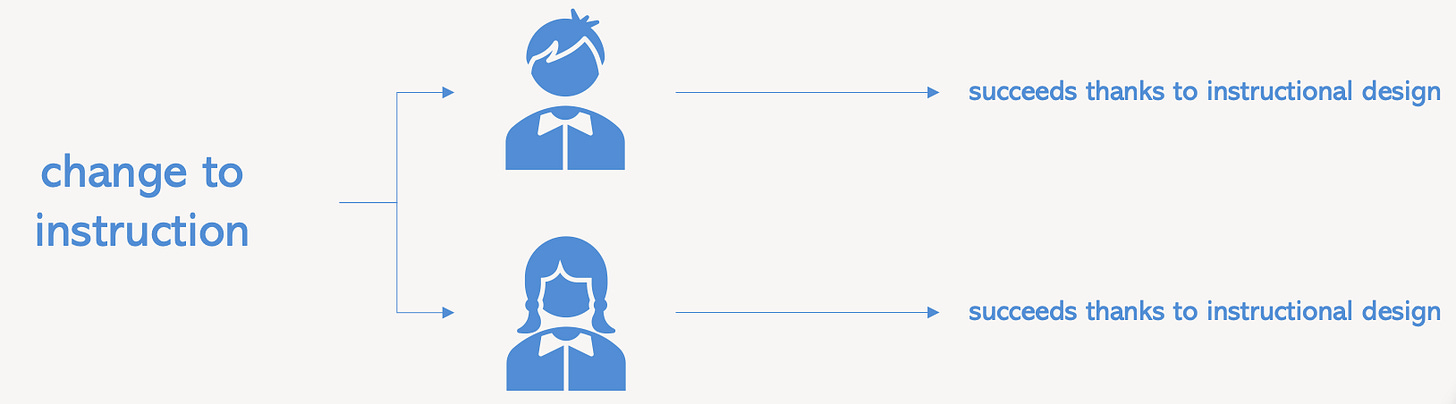

And, we’ll see how it’s possible to make changes to our instruction that more or less guarantee success for every single student in every class.

We’ll even see how each of these common explanations can, although not always, certainly very often, be reinterpreted as imperfections in instructional design – even those that we perceive as attentional issues.

So let’s dive in, starting with how to identify cognitive routines, and distinguish them from transformations.

Sometimes the line between transformation and cognitive routine is blurred.

They both involve taking some starting input, and processing the information it offers to produce some output.

The difference is that for a transformation…